Podcast Write-Up #4: On the Margin w/ Luke Gromen

A chat about the endgame of the current monetary system

Welcome to issue #4 of my mid-week podcast write-up series.

If you’ve been here for a while, you might notice that I’ve changed the name and overall look and feel of my newsletter:

I’m very happy with the new design and the new name! The thought behind the logo is “connecting the dots”, which is exactly what I try to do every weekend in my FX and Macro deep-dive. Here’s the latest issue in case you’ve missed it:

If you like this newsletter, please consider subscribing and sharing it or forwarding it to others who might be interested. I'm also on Twitter @fxmacroguy if you want to reach out.

One more thing. You seem to like newsletters, so here's a great way to discover new stuff to read for free: The Sample. They will regularly send you an issue of a different semi-random newsletter you might be interested in. If you sign up using my referral link, I get bonus points and my newsletter will be forwarded to others to check out.

Release date: 24.08.22

Host(s): Michael Ippolito @Mikelppolito_

Guest(s): Luke Gromen @LukeGromen, FFTT

Charts were taken as screenshots from the Youtube version of the podcast.

Notes

Q: Please walk us through your big geopolitical framework.

Luke starts at Bretton Woods and the two competing proposals at the time from John Maynard Keynes and Harry Dexter White.

Keynes proposed Bancor as a neutral trading/settlement asset with national currencies floating against it. The US has been running deficits for about 50 years, and with a system like the Bancor, this would not have been possible: the US would have had to sell dollars and buy Bancor, which would have weakened the dollar. This would have made the US more competitive and it would have forced greater fiscal discipline.

White proposed the system that was finally implemented: every currency is tied to the dollar and the dollar was tied to gold at 35$/ounce. In the post-war period, other economies started to run large trade surpluses while the US was running greater deficits due to the Vietnam war. Debt outstanding was about four times the size of the amount of gold holdings of the US at the beginning of the 1970s. So, in 1971 Nixon closed the gold window “temporarily”. No one knew what the dollar was worth then, effectively.

The US came to an agreement with the Saudis to price oil in dollars, which was basically the foundation of the petrodollar where dollar surpluses were recycled back into the eurodollar market and into US financial assets. The greatest US exports became dollars and treasury bonds.

From 1973 to about 2003 the dollar was kept as good as gold when it came to gold, i.e. the price of oil priced in gold remained relatively consistent during that time. Part of the reason for that was US monetary policy: if oil became too cheap, the Fed would loosen policy, and if it became too expensive, it would tighten.

In 2005/2006 China grew rapidly and overtook the US as the biggest oil importer. The US economy needed rate cuts, but the high oil prices signalled a need for the Fed to tighten significantly. When the Fed ultimately cut rates because of the housing market and the crash in the banking system, oil went from $70 to $150 in about nine months.

So, the US had a chance to go through a period of austerity, wipe out equity holders and settle the problems with capitalism, but instead, we chose to print money and backstop everything. That showed to the world that the US had given up on managing the value of the dollar relative to energy prices (or commodities in general) in favour of taking care of itself first, i.e. managing the dollar for its domestic economy instead of as a global reserve currency.

Q: Every economy in the world needs energy, and you don't want a mismatch between assets and liabilities with assets being the money supply and liabilities being your energy needs. So after going off the gold standard, there was an implicit promise to keep the dollar as good as gold for oil to balance this out. In 2008, the US broke that promise. We also broke the foreign exchange window when we confiscated Russia's central bank assets. What are the ramifications of us breaking these social contracts?

Luke thinks the consequences are far-reaching. Historically these big systemic changes have led to wars. Keeping the dollar as good as gold with regards to oil means keeping it neutral to positive in real rate terms relative to oil: if oil goes up 5% per year, you need interest rates at 5% per year. That works if the economy is under-levered, but with current debt levels, it's impossible.

The European economy is going to collapse if electricity and natural gas are going to go up. There's the fundamental tension again: the US can't afford to pay positive real rates relative to the price of energy that would be needed to bring in new supply, and the importers of energy can't afford to not get paid a positive real rate on their savings.

Historically, tensions like these have led to wars: World War I was about Germany leaving the English economic system after the panic and crisis of 1873 and the following 20-year-long depression. The British implemented liberal economics and free trade, and they offshored production to their low-wage colonies. This caused wealth inequality to increase because the working and middle class could not compete anymore. Since everyone was on the gold standard, it was impossible to print money, which led to this long depression. Germany started to run a different economic model with more centralization, and investments into their infrastructure and military. Rising competition between Germany's and the UK's economic systems led to World War I.

Luke draws a comparison to China's Belt and Road Initiative and sees parallels to what's happening currently with Russia and Taiwan. He thinks that if World War II was an extension of World War I, this can show where things might possibly be heading right now.

Sky-high inflation will lead to politicians being elected out of office, and economic sectors that have been neglected for the past 45 years will benefit: the middle and working class will have wage growth. Profit margins in real terms will rise and in percentage terms will fall. Inflation will be very high and bonds will suffer.

China, Russia and Europe will say that their economy will collapse if oil continues to be priced in dollars. Luke sees major fourth-turning type issues like major wars or collapses in creditor nations as possible consequences of these fundamental tensions that concern fundamental national security interests and are existential to survival.

Michael mentions a document by the Department of Defense from 2018 and quotes from p. 59:

The loss of more than 60,000 American factories, key companies, and almost 5 million manufacturing jobs since 2000 threatens to undermine the capacity and capabilities of United States manufacturers to meet national defense requirements and raises concerns about the health of the manufacturing and defense industrial base. The loss of additional companies, factories, or elements of supply chains could impair domestic capacity to create, maintain, protect, expand, or restore capabilities essential for national security.

Q: What is the link between monetary policy and the hollowing-out of the domestic industrial base in the United States?

Your competitiveness is a function of the strength of your currency. The US can't put a lot of trade restrictions in place because of the dollar's reserve status. But the bigger issue is the US treasury bond. From 1946-71 the dollar was the reserve currency but gold was the primary reserve asset. After 1971 treasury bonds became the primary reserve asset. Foreigners have to buy treasury bonds to store their dollars, so US deficits are “deficits without tears”: the US buys stuff for dollars from foreigners, and they use these dollars to buy treasury bonds.

Foreign countries keep their currencies weak to underprice what's produced in the US, so our ability to produce stuff gets worse and middle and working-class jobs get offshored. On the other hand, the US economy becomes massively financialized because the dollars we pay other countries get recycled back into our financial markets.

Luke cites 2011 as an example when the US was unable to build the Bay Bridge in San Francisco, so they had China build it. As for the defence manufacturing supply chain, it's similar: as long as there's no conflict with China everything is great, but China obviously hasn't had the US’ interests at heart for a long time. Politicians have so far mostly looked the other way on that issue. Covid has changed everybody's mind. To sum it up: if you're going to war with China, they shouldn't be making a lot of stuff for you, because they aren't going to sell it to you in a war.

Q: How effective have the sanctions on Russia been, especially the closing of the FX reserve window?

The closing of the FX window is a huge deal because the US basically told the world: your FX reserves in US dollars aren't safe. But it takes time for the effects to play out, and there are things happening if you're paying attention: India and Nigeria opening gold exchanges (Nigeria is the 7th biggest oil exporter), and Turkey buying energy in Rubles. These things might look random, but they are small pieces and when we look back in five years’ time or even sooner, the magnitude of closing the FX window will be increasingly obvious.

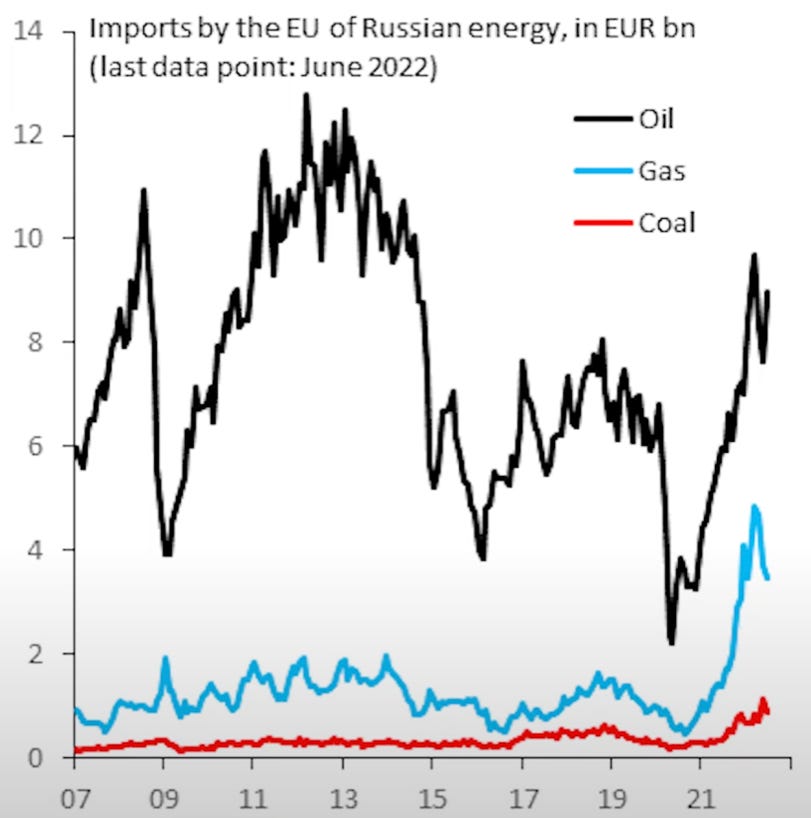

As for the sanctions hurting Russia: the sanctions have disrupted their supply chains and they are very problematic in some ways but not in others. What was really surprising to Luke was the fundamental misunderstanding of the elasticity of the energy demand: human demand for energy is infinite. Energy sanctions from the EU have blown up in their faces. China and India represent about 40% of the global population and their usage of energy per capita relative to the West is low. They could take all of Russia's energy production if it weren't for the logistical aspects. The sanctions also leave out the demand elasticity from price: if Russia's export drop by 50% but price triples, then Russia is getting more money than before. It shows up in the data: the current account for Russia is at all-time highs because they're not importing stuff from the West anymore and their revenue from energy exports is up. The West miscalculated and now has to deal with an energy crisis.

Q: What's going to happen next in Europe with energy?

Luke thinks the economy is going to collapse, people are going to freeze and die unless either:

the US starts selling dollars for euros,

the US starts selling a lot more natural gas to Europe, or

Europe starts paying Russia for oil in euros or yen.

The threat of people starving and freezing in Europe and Japan will force a geopolitical realignment that's currently unimaginable for most people.

Q: You described bitcoin as the "last functioning fire alarm”. What do you think about Bitcoin and its role with regard to the tension the Fed is under?

Luke believes Bitcoin is doing to the Fed what gold did to Volcker. He mentions an article from a few months ago by a 40-year veteran of the London Bullion Market that goes into how gold is manipulated by “paper gold”. That doesn't refer to GLD or futures but unallocated gold where people can buy large amounts with a simple phone call. That ends up being just an accounting entry that's going to be cash settled in the end. Bitcoin doesn't have this sort of unallocated market that mutes its warning alarm function. Also, it's a lot easier to buy actual Bitcoin than to buy physical gold.

Bitcoin also has a fixed supply of 21 million and it has a steady flow. It is just doing what gold would do if gold didn't have a huge paper market attached to it. It has been very early in pointing out liquidity turns.

Q: There are basically two options for central banks: 1. hike until unemployment rises and demand gets crushed, or 2. hike rates a little bit, let inflation run above target and eventually adjust the target from 2% to, say, 4-5%. What do you think about that?

It's going to be neither of those two options. The problem is the debt situation: the US had a lot of bubbles in housing and stocks, and they created an unprecedented increase in tax receipts. Even as those tax receipts were at all-time highs, they just barely covered entitlements and treasury spending. The US spends 2.8-2.9 trillion dollars in entitlements per year, treasury spending is at about one trillion. Bringing down demand will bring down inflation, but it doesn't account for secondary effects: GDP comes down, tax receipts come down and will end up below entitlements and treasury spending, which is also going to go up because a third of debt is financed at under one year and that's going to reprice higher.

The US can print money to make up for the difference: the bond market will then dictate the rate the US is going to borrow at, and that will lead to a debt-death spiral because debt is going to reprice higher the more borrowing is going on, which is self-reinforcing.

The other option is to have inflation run at 4-5% and inflate the debt away. If rates remain at 2% and inflation runs at 4-5% nobody is going to want to hold the debt. The Fed would have to buy the entire bond market to peg rates at a negative real level. The Fed's balance sheet would go from 9 trillion to something like 50 trillion in a year, the dollar gets crushed and inflation goes crazy.

Q: What are your thoughts on the relationship between the US and other countries?

The balance of power shifted from about 2015-2018. An example would be Donald Trump telling the Europeans in about 2018 that trade in energy is different from other trade and that he was wondering why the US protected them when they bought all this cheap gas from Russia. Or in 2019 he said that if the Chinese decide to take Taiwan, there's nothing the US can do about it.

If the US is an empire and acts that way, it will have to come up with soldiers to defend it. The last 20 years haven't been good for the US in that regard: taking Afghanistan with a massive financial cost and cost of human lives and then giving it back to the Taliban. Young people don't want to fight for the US and its economic system that's not in their or their families’ interests.

Michael compares the post-war period, where the G.I. bill was basically a huge transfer of wealth from the old generation to young G.I.s returning home after the war, to Covid, where only old generations profited with financial assets and real estate going up in price. He says young people feel disenfranchised, and not well represented by current politicians.

Luke thinks it's not just the youth but also the inequity of how the GFC in 2008 was handled was one of the biggest political mistakes in the history of the US: Wall Street claims to be capitalist, but there was no real capitalist solution with a wipeout of equity holders, which would have prevented all the following bubbles.

He mentions an article in The Atlantic from 2009: The Quiet Coup by Simon Johnson, a former IMF chief economist. In it, he argues that the US goes into emerging market countries, breaks up the banks and applies capitalism, wipes out the oligarchs and installs a new leadership. The US had the exact same problem as an emerging market but they decided to do the opposite.

The disenfranchisement runs deeper because capitalism is only applied to, for example, homeowners and pensioners, while the elites and policymakers get the communist treatment: privatizing gains and socializing losses.

Q: What do you expect policymakers will do over the next year to confront the domestic challenges like inflation and the geopolitical problems? And what would you be doing if you were in charge?

Luke thinks they are going to do the right thing by accident after doing the wrong things first. They are going to overtighten, create a brief crash and get inflation down to 4-5%. Something will break in the financing mechanism of the US government, and that will not be allowed to occur, so the Fed will have to turn around and expand its balance sheet again with CPI still at 4-6%. So, within the next 12 months, inflation will be in excess of 10%, which will force the Fed into yield curve control with the Fed buying a large chunk of the bond market. Inflation is going to run hot and it will be like a giant debt jubilee for holders of fixed-rate debt because wage growth will be so high. He believes there will be a period of something like three years with CPI at 12-20% that will lower debt/GDP enough for the Fed to be able to normalize policy without breaking something.

If he was in charge, he would be bold: print something like 2 trillion dollars for the next five years, invest that in semiconductor manufacturing, infrastructure, education, while the Fed keeps 10-year rates at 3% regardless of CPI or money supply. At the end of that time, debt/GDP will have collapsed, wages will have gone up massively, but the US would have strengthened its infrastructure and defence supply chains, and educated and reinvigorated its young generation. At one point the Fed can normalize policy again.

It's all underpinned by the thesis that inflation is *now* permanent, without ever explaining why for the past twenty-odd years it has been non-existent. That's the bit I just can't get.